Laurie McGinley, The Washington Post

Bald but beaming, 5-year-old Eden Oyelola yanked the long rope to ring the “victory bell” at Children’s National Medical Center last September. She was finally done with her treatment for brain cancer — surgery followed by months of radiation and chemotherapy that made her terribly ill.

At a “bell party” at her home in Upper Marlboro, Md., later that week, she gobbled down ice cream with friends and rode a pony around the back yard. Her parents exhaled in relief. “We thought she was in the clear,” her father said.

The relief was short-lived.

In January, the little girl who loved gymnastics started having seizures and losing control of her left side. She frequently stumbled. “What’s wrong with my legs?” she asked. A second surgery followed after an MRI showed that the tumor had returned, forcing her doctors at Children’s to ask whether there was anything else that would give Eden a chance to survive.

The team ultimately turned to the hottest field in medicine and a new class of drugs that has had stunning success in some adults, including former president Jimmy Carter, with even hard-to-treat malignancies. Growing ranks of pediatric oncologists are considering immunotherapy and “checkpoint inhibitors” to try to save desperately ill children.

But young patients with cancer present a special challenge. Research can seem more dangerous because of their age, and drugs that work in adults may fail for the same reason. No one can yet say with certainty whether — or to what degree — these treatments hold equal promise for children.

That allows for hope as well as, in Eden’s case, devastating disappointment.

“It’s a new horizon that we need to explore and see if it can help these kids,” said Brian Rood, Eden’s neuro-oncologist. “But we’re still learning how to use it.”

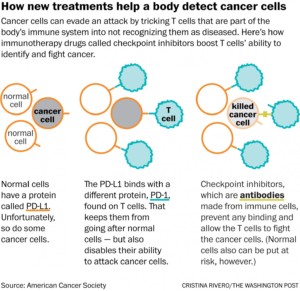

Immunotherapy, which one specialist calls “the fourth pillar of cancer treatment” after surgery, radiation and chemo, marshals the body’s immune system to fight a malignancy. As part of that approach, checkpoint inhibitors disrupt a cloaking device tumors wield to evade and suppress T cells, the foot soldiers of the immune system. Once T cells can see the cancer, they attack it just as they would other foreign intruders such as bacteria.

Four checkpoint inhibitors have been approved for adults, but they are only now undergoing broader testing in children. The lag reflects the many significant hurdles of conducting clinical trials with this age group.

Eden’s doctors set their hopes on a first-of-its-kind clinical trial led by Children’s, a study testing a checkpoint inhibitor treatment in children who have aggressive brain tumors. The complex strategy has its own set of risks; the treatment often causes inflammation and swelling, a dangerous combination in the contained space of the brain.

n describing the trial to Eden’s parents, Rood was cautious. Their daughter would need yet another surgery to reduce the size of her tumor, and there was no guarantee she would be eligible for the trial after that, or that the treatment would work.

“About the best we can say,” Rood acknowledged, “is that we don’t know that it doesn’t work.”

“Eden will be a guinea pig,” thought Eden’s mother, Sara Amare. But like her husband, Toks Oyelola, she was eager to press ahead. Both knew that the study medication, Keytruda, also called pembrolizumab, was the same one that Carter received after advanced melanoma spread to his liver and brain. Last December, following surgery, radiation and the immunotherapy, the former president announced that his cancer had disappeared.

“He was 91,” Amare said. “I thought, ‘Surely, this will work in a 6-year-old.’ ”

As a child with cancer, Eden belongs to a relatively small group. An estimated 16,000 children up to age 19 will be diagnosed with the disease in the United States this year, and it will kill fewer than 2,000. By contrast, about 1.6 million adults are expected to get a diagnosis, and more than 590,000 will die of the disease.

Pediatric oncologists complain that medicines for children are too few and too toxic, largely because drug companies focus their efforts on the adult market. Only one immunotherapy drug has been specifically approved for pediatric cancer.

“Over the last 30 years, we have had very, very few new drugs in our clinics, and we still rely on radiation and chemo,” said Michael Jensen, director of the Ben Towne Center for Childhood Cancer Research at Seattle Children’s. “When a drug is developed for prostate cancer or breast cancer or colon cancer, they will say, ‘Here, try this for kids with brain tumors.’ It really doesn’t help these underserved kids.”

Researchers have long known that children are not simply miniature adults; they are biologically different. They tend to get different cancers than adults — leukemia rather than lung cancer, for example — and even the same cancer can play out differently in their bodies.

So, perhaps, may immunotherapy. Many adult tumors have mutations caused by cigarette smoke, sunlight and other environmental insults. Once unmasked by a checkpoint inhibitor, such mutations can be seen by the immune system as “foreign” and deserving of attack. Children’s cancers, however, generally have far fewer mutations and thus may offer fewer targets, according to one theory.

Another kind of immunotherapy, called CAR-T cell therapy, is being widely tested in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the most common and once universally fatal childhood cancer. It has shown extraordinary effectiveness in treating recurrent disease.

By contrast, checkpoint inhibitors in children “may not be the home run they are in adults,” said Crystal Mackall, head of the cancer immunology and immunotherapy program at the Stanford University School of Medicine. “But it’s too early to know.”

The Oyelola family lives in a comfortable house in Prince George’s County, with a back yard big enough to accommodate pony rides on special occasions. Eden, who is obsessed with unicorns, has a 7-year-old sister, Sade, and an 18-month-old brother, Tobi.

“He chases me, then I chase him,” Eden said on a recent afternoon as the children raced around. Dressed in a shirt decorated with lions, tigers and zebras, she showed little sign of being sick, other than a little puffiness in her face and slightly shorter hair where she had surgery.

Eden and her sister Sade (Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post)

Eden and her sister Sade (Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post)

Eden’s father is a consultant for Ernst & Young whose parents came from Nigeria decades ago. Her mother is a native of Ethiopia who moved to the United States as a little girl. A wall of photographs in the family room shows a handsome and happy family.

On Halloween 2014, Oyelola remembers, “a new normal” took hold. Amare was driving their daughters home from a school parade — Eden had been dressed up as the country of Russia. Suddenly, Sade cried from the back seat: “Mommy, Eden is shaking!” Saliva foamed on her lips.

Doctors at Children’s diagnosed a febrile seizure, a not-uncommon event in childhood. But several weeks later, another seizure followed. This time, Children’s did a scan. “We see a mass,” the doctors told Amare. Brain surgery was scheduled for Christmas Eve.

Eden’s family decorated her intensive-care room with lights, wreaths and a tree. When she woke up on Christmas, she was amazed by the presents, sneaked in by nurses, and by a visit from Santa Claus himself.

Those would be the only bright spots of the holiday.

The ultimate diagnosis was that Eden had a “primitive, very rare, very unusual tumor,” Rood said, with many of the characteristics of glioblastoma. This deadly type of cancer arises from glia cells, which support brain function.

Months of radiation and chemo followed, ending with the bell party in September 2015. Late last year, the Make-A-Wish Foundation arranged for the family to go on an all-day scavenger hunt that culminated in a ride on a “unicorn” at Verizon Center. “Yes, it’s a real unicorn!” Eden declared, caressing the big white horse.

The tumor’s return in January was a crushing blow. Eden quickly had surgery and eventually entered a clinical study involving pomalidomide, a thalidomide derivative that is thought to interfere with tumor growth. She began getting violent headaches. “She could wake up in the morning and be hysterical for two hours,” her father said. And she was having three to four seizures an hour.

The doctors took her off the medicine and talked to her parents about the immunotherapy trial and another operation. “It was nerve-racking,” Rood said. Yet they had no other options.

In late May, Eden had her third surgery, which succeeded in sharply reducing the tumor and the swelling, and in easing her pain. A few days later, she celebrated her sixth birthday.

Not long after, she got a spot in the Children’s trial.

Brain and central-nervous-system tumors are the second-most-common type of childhood cancers, after leukemia. A patient’s prognosis depends on the type of malignancy, whether cancer cells remain after surgery and whether the tumor recurs.

Given the success seen with checkpoint inhibitors for some adult cancers, there is intense interest in trying them in brain tumors in patients of all ages. The hope is that the immune system will be effective at attacking the tumor and breaching the blood-brain barrier, a kind of security system that protects the brain yet also prevents many treatments from getting through.

Several pediatric trials are underway or in development, including one trying a combination of checkpoint inhibitors that New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center has set for next year.

The safety-and-feasibility trial at Children’s and other institutions is co-sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and the Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium, a network of children’s hospitals and academic medical centers that conducts early-stage studies of novel treatments. Up to 70 patients will be enrolled, ages 1 to 21, with participants given infusions of Keytruda for 30 minutes every three weeks. The treatments are slated to extend over two years.

Eugene Hwang, a pediatric neuro-oncologist at Children’s, and the other investigators are proceeding carefully because of the risks, frequently “pausing” the study to examine results and decide whether changes are needed. One of the toughest challenges in using checkpoint inhibitors or any immunotherapy for brain tumors, Hwang said, is figuring out how to produce the right level of immune response. Too weak and it won’t affect the tumor. But too strong and the swarm of T cells could trigger lethal swelling.

“I have desperation in my back yard, where kids are dying, and there’s hope the next yard over, where adults who have failed trial after trial are surviving,” said Hwang, the study chairman. “There is nothing that is going to dissuade me from trying something that has really revolutionized care for many adults.”

Eden got her first dose of Keytruda on June 22, and everything seemed fine for the first two weeks. But shortly before her planned second dose, she again began having headaches, and numbness in her left arm. An MRI showed that the mass in her head had doubled in size in barely a month.

That raised a critical issue for her physicians: Did the larger mass mean the drug had triggered the robust immune response they wanted? Or was the treatment failing and the cancer’s growth accelerating? Or some combination of both?

It was impossible to tell from the scan. Yet the answer would determine whether Eden could continue in the trial.

The doctors delayed the second dose and gave her steroids to reduce the brain swelling. That effectively negated the effects of the immunotherapy, but it was the only way to figure out what was happening as they chose how to proceed.

Her family tried to carry on with life. They all took a vacation to the beach, making sure they visited Assateague Island to see the wild ponies.

Eden seemed to be doing well, and her parents were increasingly sure she would soon get her second Keytruda dose. But on July 28, she awoke in intense pain and was rushed the 20 miles to Children’s. The tumor had gotten significantly bigger in just a few weeks and was starting to push the brain from the right side of her head toward the left. Blood and fluid also appeared to be leaking into the space between the brain and the skull.

Doctors treated Eden with high levels of painkillers and higher levels of steroids. And they sat down with her parents. Rood told them that the tumor’s fast growth was making it impossible for Eden to stay on the trial.

Take her home, Rood suggested, and make her as comfortable as possible.

“I can’t accept that,” Amare said later, even as she talked about going “the God route.” At her request, pastors from her Ethiopian Orthodox church have come to pray for her daughter.

Her husband is similarly torn. The doctors, he said, “don’t expect a miracle to happen. But I do.”

Eden still romps through the house and plays with her dogs, Winter and Summer. On a recent afternoon, bored for the moment, she climbed onto her father’s lap and whispered in his ear to take her to Target.

She wanted to get more Twozies to add to her already sizable collection of the toy babies and pets.

“Okay,” Oyelola said with a smile. “Let’s go.”

Photo of Eden Oyelola: Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post